For downloadable PDF of the essay, please click here

JULIKA LACKNER’S NEW PAINTINGS by Jeremy Gilbert-Rolfe (September 2013)

My friend John Baldessari and I go around the galleries nearly every Saturday afternoon, and we often divide the artists whose works we’ve seen that day into those who seemed to enjoy making their work and those who didn’t. Julika Lackner enjoys making her work. It shows in the consistency of each painting’s tone and application, and in all that undermines and plays around with that consistency.

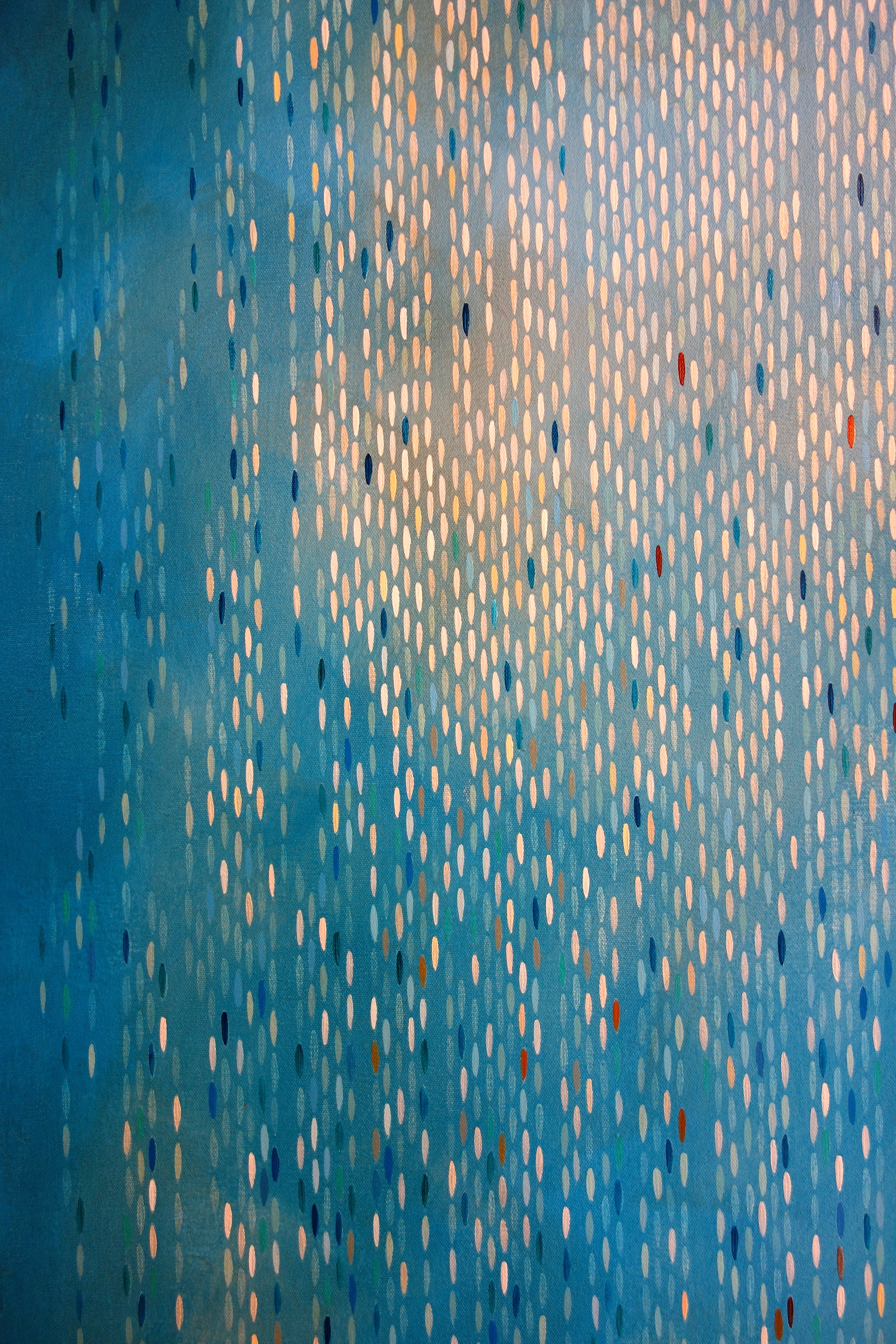

Julika Lackner, Spectral Phase #4, 2013, Acrylic, oil + alum-silver on canvas, 96"x72"

The titles of the two biggest paintings in the show, Spectral Phase #4 and Spectral Phase #5, refer at once to the color generated by the metallic leaf she uses in her paintings and to the fact that the Santa Barbara landscape that was clearly represented in her earlier work has now become a ghost: a spectral presence there not so much to be discovered if you look for it, but rather to jump out at you from a field, or depth, at which you’re looking closely. Spectral Phase #4 and Spectral Phase #5—and most of the rest of Lackner’s more recent work—are precisely fields which are also depths at almost all times, containing or made out of movements into and across themselves, and in the case of the larger paintings allowing the viewer, because of their size, to be in a pleasurably uncertain relationship to a body that is made of a surface that is almost entirely a depth while filling a space that a human can occupy.

Julika Lackner, Spectral Phase #5, 2013, Acrylic, Oil, and Alum-Silver Leaf on Canvas 96"x72"

In the paintings there are only two circumstances in which depth gives way to surface, one relative and one absolute. The metallic sheet reflects light back from the painting in a more explicit way than oil paint on a white ground does by itself. One is accordingly aware that the surface is tangible and reflective and therefore a thing. But metallic sheet is never entirely not a depth, one can’t help looking into as well as at reflective surfaces, which is why gold is so useful to religious painting—it’s at once dense and deep, and of course there’s a value thing involved when religion comes into play too. So the extent to which depth gives way to surface when we see the glittery metallic sheet is relative. The absolute sense is a function, here, of the micro as opposed to the macro. The little boats are meant to be seen as such, things floating on a liquid depth. They have become of course almost signs or patches of light, functioning almost like brush-strokes, but they are for sure the only opaque things in the paintings. Here’s a thought: the human body is the opposite, a single organ (the skin) envelops everything except for a small number of openings, or depths. The rest of the time the surface of our own bodies never gives way to depth, precisely the opposite relationship between the micro and the macro found in Lackner, and maybe in landscape in general when it’s mostly made up of water and air. In the painting a macro version of surface which is relative and in the body the skin as an absolute, in the painting the boats as a micro which is an absolute opacity where in the human body that is where we find the relative rather than absolute surface, one looks into eyes as much as at them.

David Hockney, “A Bigger Splash”, 1967, Acrylic on Canvas, 95.5”x96”

Lackner has been preoccupied with natural light since she was a student, always in a way that frustrates any search for an obvious precedent in the history of landscape painting. One reason for this is that she consciously tries to see the world as the naked eye might see it were it not conditioned by color photography. Hers is not the kind of recognizably southern California color with which David Hockney works, which is very much the kind of coloration that Hollywood or just color film in general, teaches us to see in nature. In a way one might also say it’s the opposite of Hockney’s. If there is a question as to whether the Hollywood version, which is a photograph, has taken over our sense of what is actually there, one might say Lackner wants to have a look at what it would be like if we resisted it and Hockney has made great art out of explicating and enjoying it—for he too is a great example of a painter who has a good time in the studio.

Julika Lackner, “To the Valley”, 2005, Oil on Canvas, 72” x 60”

Lackner spent a year or more not so long ago scrupulously studying the color of the night sky, figuring out what the colors in it were and then going inside and putting them on a small canvas that she kept adjusting until it would disappear into the sky if one held it above one’s head, with results that show that the sky is much less red in human perception than in any color photograph.

Julika Lackner, “Bernauer Strasse”, 2001, Oil on Canvas, 24” x 31”

The unfamiliarity of her palette also, I think, comes from its having been conditioned by Berlin as much as by Santa Barbara. Her very earliest (student) works include paintings of the inside of U- and S-Bahn stations, gloomy interiors with some yellow artificial light and the intense but bleak white light of the north making some appearance through the stairwell. I think the idea of a foreground and a background that could both be indeterminate, and in which the light came primarily from the far distance, is one that has stayed with her. I note, in groping for a precedent that confirms my suspicion, that the space she was developing (or finding) in the U-Bahn stations has a precedent in the landscape paintings of a northern painter such as Ferdinand Hödler.

Ferdinand Hödler, “Thunnersee with Reflective Mirroring”, 1909, Oil on Canvas, 26.5” x 36”

Hödler’s Thunersee with Reflective Mirroring (1909), for example, is a landscape in which the light comes from behind the mountains, casting the side of them we see into shadow. As with Lackner’s train station, a distant light source and gloom in the foreground which one may find oneself staring into as much as at. She did not know the Hödler when I brought it up with her by the way, I am talking here only of what gets to be in one’s head if one’s around it at a formative age. (Which raises the question, not to be further pursued here, of whether anyone who grows up in California ever has a chance of experiencing the state’s coloration directly, given the inevitable prior and simultaneous presence of the photographic version throughout any of the state’s natives’ childhoods.) I think Lackner uses the more intense light of Berlin (when the sun’s out) to un-think the palette conventionally and habitually associated with California, in which she’s now lived for quite a long time.

Detail: Julika Lackner, Spectral Phase #4, 2013, Acrylic, Oil, and Alum-Silver Leaf on Canvas, 96"x72"

Of course, as has already been observed, in the new paintings there are no longer many signs of where the color and space reimagined by the painting were found. California as a surface is not immediately apparent, as it was in her earlier paintings. The crowds of boats that are such an important part of her paintings have become more like a pattern, too impossibly regimented to immediately suggest the rhythm of the sea, as was the case before. Instead, Spectral Phase #4 and Spectral Phase #5 make us think or better feel our way into and around a more abstract surface that is also a depth, neither water nor air nor neither. The rows of little boats respond now as much to the geometry of the canvas as to the irregularity of the depth over which they are suspended, in some instances seen by us between a fog (or radiance, light dispersing) which covers them and the blue beneath them. There is a more complex relationship between how we look and what we look at than in her previous paintings.

The last time Lackner had a show in Santa Barbara Josef Woodard described her paintings as ones in which “The real, the metaphysical and the painterly craftily merge.” By ‘real’ I think he meant ‘things’ (as in the Latin word ‘res’), and by ‘metaphysical’ more or less what we all mean by it: ‘ideas’, and I’ll rephrase it here to describe these new works which, while continuous with what she was doing before them, move this moving somewhere else, by all means craftily, certainly in a way that is painterly.

Lackner’s new paintings bring drawing and color much closer together than in her previous work in as much as outline plays almost no part anywhere, hence the virtual disappearance of ‘things’ in the usual sense of stuff like houses and rocks and streets. Drawing is now much more a function of the boats as streams of movement, varied in intensity and in regard to the atmosphere that envelops them, or doesn’t, line a matter of direction rather than boundary, volume, in these new paintings, only present as depth without a clear limit. The question of the ‘thing’ is displaced into the question of surface and object. One recognizes these tiny signs that are the size of brush-marks as boats, one is aware that the painting is reflecting light, that one is sharing a space with it and that one is not seeing it only as a pictorial space but rather something to which one’s senses respond because one is actually in its space and it in one’s own. The metaphysical, as in all paintings generally including those about which Josef Woodard wrote, involves the logic of the senses as much or, in a critical way, even more, than logic as number and hypothesis. Even more because art is one place where our senses get to use thought against itself: art plays with logic, not the other way around. In these newer paintings everything has been brought closer together. There’s nothing you can’t look into as much as look at, and when one does one is made to see that they are the same thing. A depth inseparable from a perception of surface, within it an array of color made mobile by being here concentrated and there dispersed, a space that extends away from the spectator who looks at it.

Joseph Wright of Derby, “Two Boys by Candlelight, Blowing a Bladder”, ca1767, Oil on Canvas, 36” x 28 3/8”

Silver leaf was famously used by the English painter Wright of Derby as under-painting in pictures of glass, and elsewhere in the eighteenth century ubiquitously used in the same way in paintings of clouds. That’s where Lackner found it. If she uses this (pre-modernist) device to exaggerate what painting’s white ground usually does, which is to guarantee that the space of the painting is, as Cézanne put it, already deep, while at the same time emphasizing the materiality of the surface, then this would be to focus (if that is the right word) our attention on what has always been the case with her work. She has always been preoccupied with the aspects of the perceived which are not physical things: light; atmosphere; fog; reflection; movement. Her newest works bring the physical into a convergence with the metaphysical in which the former is not represented but present, but not as a thing but as a ghost, while the paintings as surfaces are in another sense more physical than ever, and the latter is inseparable from anything there because those same surfaces disappear into the confusion caused by a hard to grasp continuity between partial reflectivity and space painted with a careful attention to uncertainty, a precondition for enjoying Lackner’s latest extension of the premise that the space of painting is always already deep—as with the space of thinking, or metaphysics if you like.

1 Josef Woodard. “Looking Down Thinking Up- Julika Lackner presents a look at urbanscapes as viewed from an air traveler’s perspective.” The Santa Barbara News Press Scene Magazine (March 27, 2009) p.6

Copyright Jeremy Gilbert-Rolfe, Los Angeles, September 2013